Author: R&D Team, CUIGUAI Flavoring

Published by: Guangdong Unique Flavor Co., Ltd.

Last Updated: Feb 10, 2026

Anatomy of Flavor

In the sophisticated world of food and beverage manufacturing, “flavor” is frequently misunderstood as a simple interaction between a liquid or solid and the tongue. To the layperson, flavor is taste. To the professional flavorist, chemist, and sensory scientist, however, flavor is a complex, symphonic integration of disparate sensory inputs. It is a neurological construct born from the convergence of gustation, olfaction, somatosensation, and even audition and vision.

To create a product that truly resonates with consumers—one that commands not just an initial purchase but long-term brand loyalty—manufacturers must move beyond the “taste bud” paradigm. We must embrace the science of Multisensory Flavor Perception. This technical exploration delves into the physiological, chemical, and psychological mechanisms that define how we experience food and how these insights can be harnessed to innovate in flavor development.

The human tongue is equipped with taste receptor cells (TRCs) housed within papillae. These receptors are categorized by their ability to detect five primary modalities: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. However, these provide only the “skeleton” of a flavor profile. The “flesh”—the nuance, the identity, and the character—comes from the olfactory system.

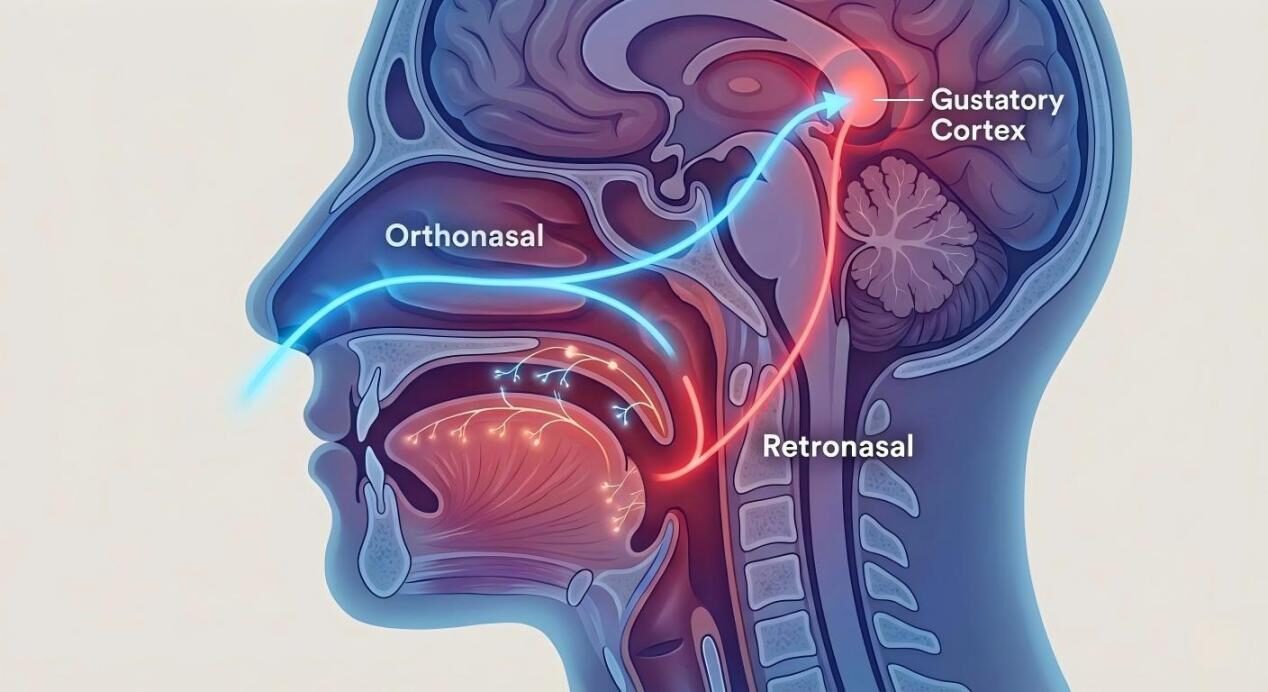

There are two distinct pathways for olfaction, and they play vastly different roles in the consumer experience.

Interestingly, the brain processes these two inputs differently. A smell that is pleasant orthonasally (like certain cheeses) might be perceived as quite different or even “stinky” retronasally. As flavor manufacturers, we must optimize for the retronasal experience, ensuring that the aroma released during consumption matches or enhances the initial sniff.

Citation 1: According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the integration of taste and retronasal olfaction occurs in the orbitofrontal cortex, creating a unified perception that the “flavor” is located in the mouth, despite much of the sensory data originating in the nasal cavity.

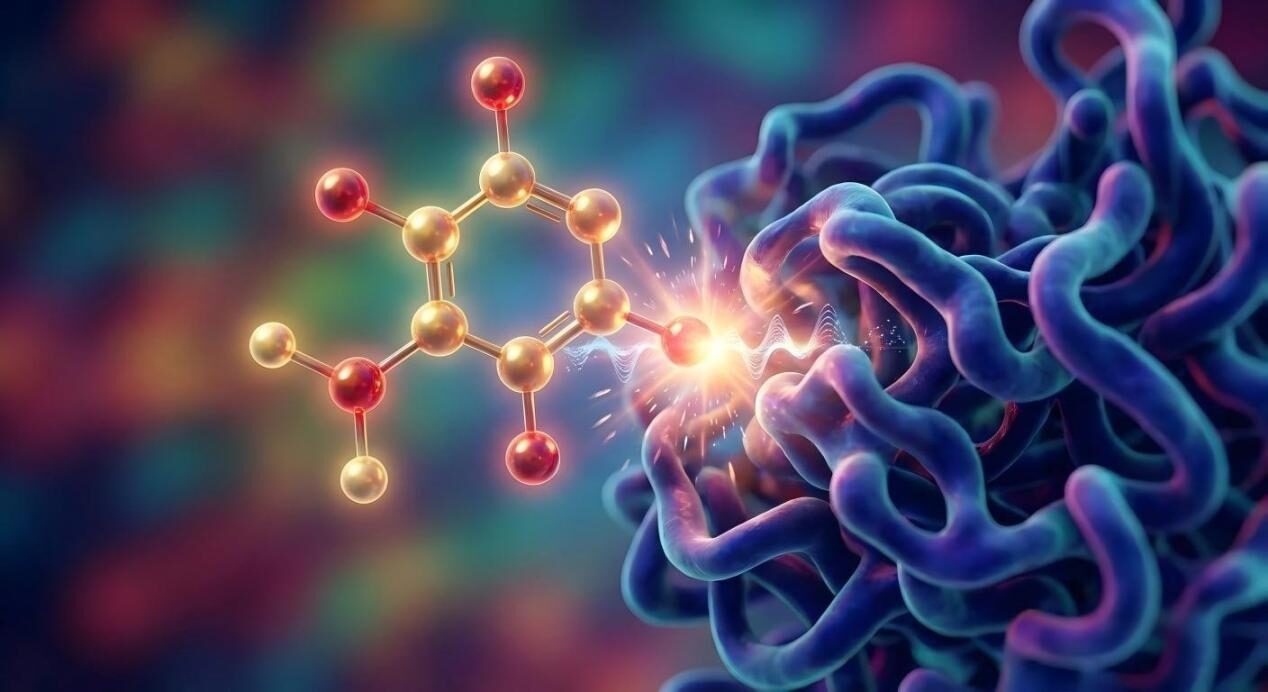

At the molecular level, taste is a lock-and-key mechanism.

For a manufacturer, understanding the specific receptor targets allows for the use of allosteric modulators. These are compounds that don’t have a taste themselves but change how a receptor responds to a tastant—for example, a “sweetness enhancer” that makes a small amount of sugar feel like a lot more.

Often overlooked in basic flavor discussions is chemesthesis—the chemical sensitivity of the skin and mucous membranes. This is not “taste” in the traditional sense; it is a somatosensory experience mediated by the trigeminal nerve (V cranial nerve).

Capsaicin from chilies or piperine from black pepper interacts with TRPV1 receptors. These are technically heat-sensing receptors. When they are triggered by chemicals, the brain literally thinks the mouth is on fire. This “pain” triggers the release of endorphins, which is why many consumers find spicy foods addictive.

Menthol, or more modern synthetic cooling agents like WS-3 or WS-23, interacts with TRPM8 receptors, which usually detect cold temperatures. In beverage formulation, these are used to provide a “refreshing” sensation that lingers long after the liquid has been swallowed.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is not just a visual or auditory element. When CO2 dissolves in the mucous membranes, it is converted into carbonic acid by the enzyme carbonic anhydrase. This stimulates the trigeminal nerve, providing that characteristic “bite” or “tingle.” In the absence of this chemesthetic input, a soda feels “flat” and the flavor profile is perceived as duller and sweeter.

A flavor is only as good as its release. A high-quality strawberry flavor will perform differently in a gummy candy (high sugar, low water), a yogurt (high protein, high fat), and a clear beverage (high water, low solids).

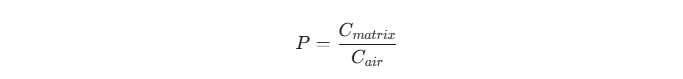

The release of a flavor molecule into the headspace (the air in the mouth) is governed by its partition coefficient, P :

Where C represents the concentration of the flavor compound. Compounds with a high affinity for fat (lipophilic) will be released slowly in a high-fat product, leading to a long, lingering aftertaste. In contrast, they will “flash off” quickly in a water-based product.

Proteins, particularly plant-based proteins like pea or soy, are notorious for “flavor scalping.” They have hydrophobic pockets that can bind to flavor molecules, preventing them from being released in the mouth. This results in a “muted” flavor profile. Furthermore, these proteins often contribute bitter or “beany” off-notes that must be chemically masked.

The Molecular Dance

The field of Gastrophysics, led by pioneers like Charles Spence, has proven that our visual perception significantly overrides our taste buds.

If you give a consumer a cherry-flavored drink but color it orange, a significant percentage of people will identify the flavor as orange or peach. The brain uses visual cues to set a “sensory template.” When the reality contradicts the template, the brain experiences “prediction error,” which can lead to a lower liking score for the product.

Research shows that increasing the intensity of a food’s color can increase the perceived intensity of its flavor by up to 10-15%, even if the flavoring concentration remains identical. This is why “Neon” colored snacks or drinks often feel more flavorful than their “natural” looking counterparts.

For the flavor manufacturer, the move toward “Clean Label” and natural colors (like beet juice or turmeric) presents a challenge. Natural colors are often less stable than synthetic dyes (like Red 40). They can degrade under UV light or change color with pH shifts. Ensuring that a flavor remains visually consistent throughout its shelf-life is a critical technical requirement.

We don’t often think of “hearing” our food, but audition is a primary indicator of texture and quality.

The sound of a potato chip or a biscuit breaking is a high-frequency sound (typically around 5 kHz). This sound informs the brain about the product’s “crispiness” and “freshness.” If the sound is muffled (dull or low-pitched), the brain interprets the product as stale, even if the chemical flavor is perfect.

In the beverage industry, the sound of a can opening or the “fizz” of bubbles reaching the surface acts as a conditioned stimulus. It triggers salivation before the first sip is even taken. This is why “sound engineering” is becoming a part of the packaging and formulation process.

Citation 2: As noted by the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT), the interaction between texture, sound, and flavor release is a key challenge in formulating plant-based proteins, where the “beany” off-notes are often trapped or amplified by the protein matrix, requiring specific textural modifications to ensure a “clean” sensory break.

Texture is often the “unsung hero” of the flavor experience. It dictates how long a food stays in the mouth and how it interacts with the tongue’s surface.

High-viscosity liquids (thick shakes) coat the tongue and slow down the migration of flavor molecules to the receptors. This “damping” effect means that thicker products usually require higher dosages of flavoring to achieve the same perceived intensity as a thin liquid.

While rheology looks at how a substance flows, tribology looks at the friction between the tongue and the palate. This is essential for:

By using hydrocolloids (like xanthan gum or pectin) and specialized “mouthfeel” flavors, we can mimic the lubricating properties of fat, tricking the brain into perceiving a richer, more indulgent product.

Modern flavor manufacturing isn’t just about adding “Strawberry” or “Chocolate” notes. It’s about managing the total sensory environment through Flavor Modulation.

Many functional ingredients—like caffeine, vitamins, or plant proteins—are inherently bitter. Bitterness maskers work by either:

With the global push for sugar reduction, we use “Sensory Enhancers” (FEMA GRAS compounds) that enhance the perception of sweetness. These compounds can make 5% sugar taste like 10%, allowing manufacturers to cut calories without sacrificing the “body” and “mouthfeel” that sugar provides.

Umami (savory) is unique because of the synergistic effect between Glutamates and Nucleotides (like IMP and GMP). When combined, the perceived umami intensity is not additive; it is multiplicative. This is a vital tool for creating “clean label” savory products without excessive salt.

Citation 3: The Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association (FEMA) provides rigorous safety assessments and “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS) status for these modulating compounds, ensuring they meet the highest global safety standards for food additive innovation.

Laboratory Precision

How does a manufacturer ensure these multisensory elements survive the rigors of industrial processing?

Many flavor molecules are extremely fragile. They are sensitive to heat, oxygen, and light. To protect them, we use:

A flavor that tastes great on day one must also taste great on day 180. We perform “Accelerated Aging” tests, subjecting products to high heat and humidity to simulate months of shelf-life. We then use GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) to see which molecules have degraded and adjust the formulation accordingly.

Despite all our laboratory equipment, the ultimate judge of flavor is the human being.

Professional flavor manufacturers use “Trained Panels”—individuals who have been calibrated to detect minute differences in flavor attributes. They use techniques like:

While trained panels tell us how a product tastes, consumer panels tell us if they like it. We use “Hedonic Scales” to measure preference and “Just About Right” (JAR) scales to identify if a specific attribute (like saltiness) needs adjustment.

The future of flavor is data-driven. We are now using Artificial Intelligence to predict “Crossmodal Success.”

By feeding decades of sensory data into AI models, we can predict how a new sweetener will interact with a specific fruit acid profile. This reduces the “trial and error” phase of development, getting products to market faster.

We are exploring how digital environments (Virtual Reality) and soundscapes can be used to enhance the flavor of physical food. For example, playing “high-pitched” music has been shown to enhance the perception of sweetness in chocolate. As we look toward 2030, the “product” may include a recommended playlist or visual filter to optimize the flavor experience.

Citation 4: Industry insights from Nature Portfolio (Scientific Reports) suggest that the future of food design will involve “neuro-gastronomy,” where flavors are tailored to individual genetic predispositions (e.g., TAS2R38 gene variants for bitterness) to create personalized sensory experiences that cater to “supertasters” and “non-tasters” alike.

To illustrate these principles, let’s look at the development of a plant-based meat alternative:

The “Beyond Taste Buds” philosophy is what separates a standard ingredient supplier from a strategic innovation partner. By understanding that flavor is a multisensory construct—influenced by the chemistry of aroma, the physics of texture, the psychology of color, and the biology of chemesthesis—we can create food and beverage experiences that are truly unforgettable.

At our core, we don’t just manufacture flavors; we engineer sensory memories. Whether you are looking to revitalize a classic product or disrupt the market with a revolutionary new functional beverage, a multisensory approach is your roadmap to success.

The Final Product

Are you ready to elevate your product’s sensory profile? Our team of flavor chemists and sensory scientists is available for technical consultations to help you navigate the complexities of multisensory formulation.

Partner with us to:

| Contact Channel | Details |

| 🌐 Website: | www.cuiguai.cn |

| 📧 Email: | info@cuiguai.com |

| ☎ Phone: | +86 0769 8838 0789 |

| 📱 WhatsApp: | +86 189 2926 7983 |

| 📍 Factory Address | Room 701, Building 3, No. 16, Binzhong South Road, Daojiao Town, Dongguan City, Guangdong Province, China |

Copyright © 2025 Guangdong Unique Flavor Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.