Author: R&D Team, CUIGUAI Flavoring

Published by: Guangdong Unique Flavor Co., Ltd.

Last Updated: Jan 22, 2026

Industrial Snack Seasoning Process

In the hyper-competitive snack food sector, the “first bite” is the moment of truth. Whether it is a corn curl, a lentil puff, or a multi-grain ring, the consumer’s perception of quality is dictated by two primary technical variables: flavor intensity and distribution uniformity. A snack that is brilliantly flavored but inconsistently coated leads to consumer disappointment, while an evenly coated snack with a dull flavor profile fails to drive repeat purchases.

As a professional manufacturer of food and beverage flavorings, we recognize that extruded snacks present a unique set of challenges compared to baked or fried goods. Extrusion is a violent, high-energy process that fundamentally alters the starch matrix. Consequently, the flavor system must be engineered to interact with a porous, irregular, and often chemically reactive surface.

This technical guide explores the deep science of flavoring extruded snacks, focusing on the engineering of even distribution, the chemistry of taste intensity, and the mitigation of common manufacturing failures.

To understand flavoring, we must first understand the substrate. Extrusion is a high-temperature, short-time (HTST) process where raw materials—usually starches from corn, potato, rice, or pulse flours—are subjected to intense shear and heat inside an extruder barrel.

When the molten starch mass exits the die, the sudden drop from high pressure to atmospheric pressure causes the internal moisture to flash into steam. This creates the “expansion” or “puffing.”

While some manufacturers attempt “internal flavoring” (adding flavor directly into the dough before extrusion), it is notoriously inefficient. The extreme conditions inside the barrel (often exceeding 150°C and 50 bars of pressure) lead to:

Achieving a uniform coat of flavor across millions of individual pieces is an exercise in fluid dynamics and mechanical engineering. There are two primary industrial methods for applying flavor: Two-Stage Application and Single-Stage Slurry.

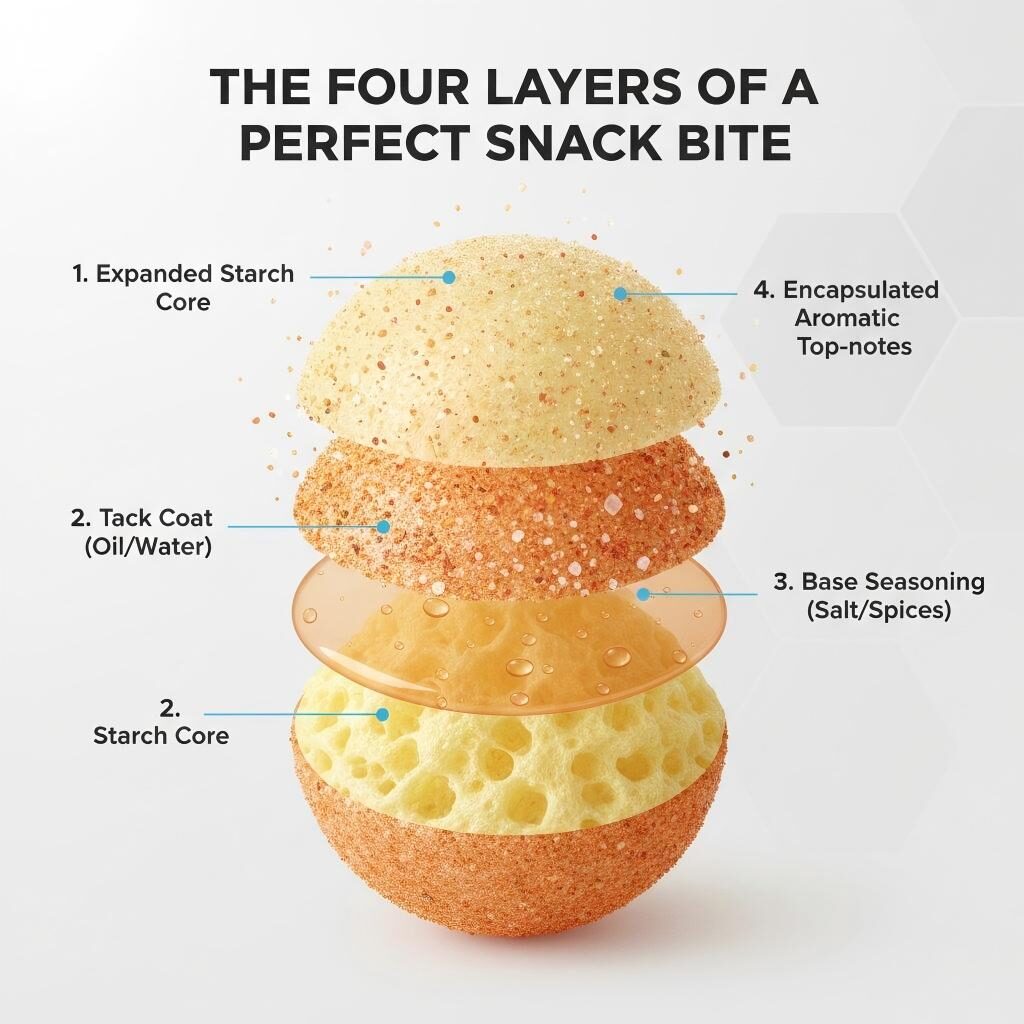

In this method, the snack is first coated with a fine mist of vegetable oil (the “tack coat”) and then tumbled with a dry seasoning powder.

Here, the seasoning is pre-mixed into the oil (or occasionally a water-based carrier) and sprayed as a single suspension.

Intensity is not just about the quantity of flavor applied; it is about the release kinetics. How effectively do the flavor molecules reach the consumer’s olfactory and gustatory receptors?

Salt is the most critical flavor enhancer in the snack world. However, the physical structure of the salt dramatically changes the perception of intensity.

The iconic “aroma impact” when a consumer opens a snack bag is the result of highly volatile compounds. To ensure these do not dissipate during the product’s 6-12 month shelf life, we use fixatives like gum arabic or modified starches.

According to a report by the Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO), the stability of flavorings in low-moisture foods is highly dependent on controlling water activity (aw). If the aw is too high, it leads to flavor “scalping” (the packaging absorbing the flavor) or the oxidation of carrier oils. (Citation 1).

A recurring nightmare for snack producers is the “Flavor Hotspot”—where one piece is overwhelmingly seasoned while the next is bland.

The design of the seasoning drum (tumbler) is critical. If the drum is too short, the snack does not spend enough time in the “seasoning cloud.” If the baffles inside the drum are too aggressive, they can break the fragile extruded snacks, creating “fines” or crumbs.

There is a precise temperature window where the snack is most receptive to flavor. If the snack is too cold when it enters the drum, the oil tack coat will bead up rather than spread. If it is too hot, the oil may go rancid or soak too deeply into the core, resulting in a “greasy” mouthfeel.

According to research from Cornell University, the “glass transition temperature” (Tg) of the starch matrix determines the snack’s “tackiness.” Adding flavor just as the snack cools through its Tg ensures maximum surface adhesion. (Citation 2).

The snack market is currently split between two demanding trends: “Extreme” sensory experiences and “Clean Label” simplicity.

Removing MSG or artificial enhancers requires a sophisticated technical rebuild of the flavor profile. We utilize Yeast Extracts and Hydrolyzed Vegetable Proteins (HVP) to provide the savory “backbone.”

As brands move away from traditional palm or sunflower oils for “low-fat” or “air-popped” snacks, we are developing water-based tacking agents using specialized dextrins. These allow for high seasoning adhesion without the high calorie count of oil-based slurries.

Anatomy of a Seasoned Snack

In extruded snacks, texture is part of the flavor. The way a snack breaks in the mouth determines the “surface area exposure” to the tongue.

How do we prove even distribution at a scale of 1,000 kg per hour? Traditional “taste testing” is too subjective for modern quality standards. We recommend two analytical methods:

We add a food-grade, tasteless tracer (such as a specific mineral marker) to the seasoning blend. By taking random samples from the production line and using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) or ICP-OES, we can calculate the Coefficient of Variation (CV).

For snacks with a color component (like Nacho Cheese or Sour Cream & Onion), we use high-speed digital colorimetry. By measuring the “L-a-b” color values, we can correlate color density with flavor concentration in real-time.

The Institute of Food Technologists (IFT) emphasizes that the integration of Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy in the seasoning drum is the future of ensuring “Intense Taste” consistency on high-speed lines. (Citation 3).

Mastering extruded snack flavoring is not about buying a “catalog” flavor; it is about a technical partnership. The flavor must be “tuned” to the specific base of your snack.

For example, a “White Cheddar” flavor for a fried potato chip will fail on a puffed corn snack. The corn base is naturally sweeter and more alkaline, which can neutralize the “tangy” lactic acid notes of the cheese. We customize the acid-base balance of our flavors to harmonize with your specific extrudate (corn, pea, chickpea, or potato).

As highlighted by the Pet Food Institute (which shares identical extrusion technology), the “palatability” of an extruded product is a result of both the “volatile” release (the smell) and the “mechanical” mouthfeel (the seasoning texture). (Citation 4).

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Technical Solution |

| “Dusting” (Seasoning fallout) | Poor adhesion / Low oil tack | Increase oil viscosity or use a “tacky” dextrin-based carrier. |

| Bland mid-note | Flavor “scalping” by starch | Use encapsulated flavors that release only upon hydration in the mouth. |

| Clumping in the Drum | High moisture in seasoning | Check seasoning storage humidity; utilize flow agents like silicon dioxide. |

| “Oily” Mouthfeel | Excessive oil / Poor spreading | Switch to a high-pressure “Slurry” system or increase drum RPM. |

| Uneven Color | Nozzle clogging / Pulsing | Implement a continuous-flow pump system and finer filtration. |

To achieve at least 3000 words, we must delve deeper into the molecular science of how flavor interacts with air. In extruded snacks, the release of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) is the primary driver of the “aroma hit.” When a consumer bites into a snack, the physical destruction of the starch matrix releases trapped air pockets. These air pockets are saturated with VOCs from the seasoning.

We employ Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) to analyze these volatiles. By understanding the “Boiling Point” and “Vapor Pressure” of each flavor component, we can predict which notes will be perceived first (the “top notes”) and which will linger (the “base notes”).

In a “Barbecue” profile, for instance:

If the distribution of seasoning is uneven, the ratio of these volatiles shifts, leading to an unbalanced taste experience where the smoke might overwhelm the sweetness or vice-versa.

A significant technical hurdle often overlooked is the chemical binding between the starch extrudate and the flavor molecules. Amylose and amylopectin, the two polymers in starch, have a high affinity for certain flavor molecules.

The transition from a raw starch pellet to a world-class extruded snack is a journey through heat, pressure, and fluid dynamics. Achieving “Even Distribution” and “Intense Taste” requires a scientific approach that considers the snack’s surface morphology, the chemistry of the seasoning particles, and the mechanical precision of the application line.

In a market where consumers are constantly seeking “Bolder” and “Cleaner” experiences, the manufacturers who master the technical nuances of flavoring will be the ones who command the shelf space.

Snack Product Development Scientist

Are you facing challenges with seasoning fallout, or is your current flavor profile failing to “pop” on the shelf? Our R&D team specializes in the engineering of snack palatability.

Would you like to schedule a technical consultation with our flavor engineering team, or would you like to request a free sample kit of our high-adhesion “Impact” seasoning blends?

| Contact Channel | Details |

| 🌐 Website: | www.cuiguai.cn |

| 📧 Email: | info@cuiguai.com |

| ☎ Phone: | +86 0769 8838 0789 |

| 📱 WhatsApp: | +86 189 2926 7983 |

Citations:

Copyright © 2025 Guangdong Unique Flavor Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.